It’s never as much to fun read about movies as it is to watch them, so I’ll keep the spoilers to a minimum and hope you catch some of these that you might have missed. But they can be a joy to write about, and these 20 are the ones that most compelled me to ramble, reflect, and remember.

– 20 –

Licorice Pizza

Paul Thomas Anderson’s nostalgia-drenched feature takes its beat from Alana Haim, who makes us believe in her 25-year old character’s sheltered craving for the turbulent adolescence she never got to have. Her chance comes with Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman), a baby-faced – yet over-the-hill – teen actor whose confidence draws her hand-in-hand through the San Fernando Valley of the early ‘70s, sprinting from one shortsighted scheme to the next, all of which are keeping Gary in perpetually arrested development. He’s not the only one; as the decade-to-come’s seismic changes begin to seep in through the societal cracks, every character here seems hopelessly beholden to the misguided boomer years that came before, and Anderson is just as unwilling to shy away from the generation’s cringier (and outwardly racist) details as he is to clean out the dirt and grime from the aged celluloid. Amidst all the throwbacks are some of the most expertly staged scenes of the year, the spotlight falling on a vehicular getaway that encapsulates how the film’s thrillingly backwards momentum still manages to work a modern-day charm.

– 19 –

The Tragedy of Macbeth

Perhaps meant to be more studied than consumed, Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, unlike most of his co-directing efforts, feels almost closer to art school than arthouse. But there’s a lot to enjoy in the study: from how the aspect ratio tightly supplements the suffocating close-ups and vertically oppressive set design, increasing our claustrophobic enthrallment; to how leads Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand commit to the natural poise and cadence of their introductions even when they dig into the timbre of their soliloquies; to how the unnerving editing allows the Weird Sisters (played to contorted perfection by Kathryn Hunter) more gravity than any other element of the picture, while maintaining their disturbing effervescence. Rather than avoiding comparisons to other Macbeth adaptations, Coen practically welcomes them, whether it’s treading on Welles’s and Kurosawa’s black and white domain, or nodding to plot-furnishes shared with Polanski; they certainly don’t hurt, as this shadowy stage-play combines all influences with its ethereal vision, and carves out a niche for itself unlike any version we’ve seen before.

– 18 –

Petite Maman

It’s almost an appropriate power-move to follow-up her previous feature with this one, as the title of Celine Sciamma’s latest hints at more than its plot. This feels intentionally like the slightest of her films to date, not just narratively, but in every respect – locations, dialogue, artistic breadth, and especially in the cast. Child actors Josephine and Gabrielle Sanz carry the majority of screen-time, and their precociously understated performances deepen the resonance of a simple story wherein two young girls enjoy the few days they have to spend together. With a limited palette, the choices Sciamma makes are exquisite, from the persistently dim lighting to an unembellished use of autumnal tones – things less assured filmmakers might act differently on, but here feel just right.

– 17 –

Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

If you weren’t aware of just how momentous the Harlem Cultural Music Festival of 1969 was…well, neither was Questlove, not until the producers dropped forty hours of footage on his lap to sift through, with the goal of piecing together a worthy recreation of the festival’s most memorable numbers. We’re lucky that he did, or we’d still be bereft of this stunning showcase of once-lost live performances from a jaw-dropping, now-legendary lineup of talent. If you still haven’t seen it, don’t look anything up and go in blind; you’ll enjoy the surprise and anticipation over each new performer who takes the stage, many of them familiar, but all captured in a refreshingly different energy (with my personal favorite coming at the hour and ten mark) as they celebrate being part of something too pure for their day. Thompson doesn’t stop there; he ambitiously splices in raw reactions from the Harlem of the ‘60s, juxtaposed with just-as-raw retrospectives from the present, to churn our emotions and tune in our vibe with the crowd that fills the streets. And he does so without ever sacrificing the actual music; it all somehow harmonizes and amplifies the revolutionary song of voices once ignored – now finally immortalized after half a century.

– 16 –

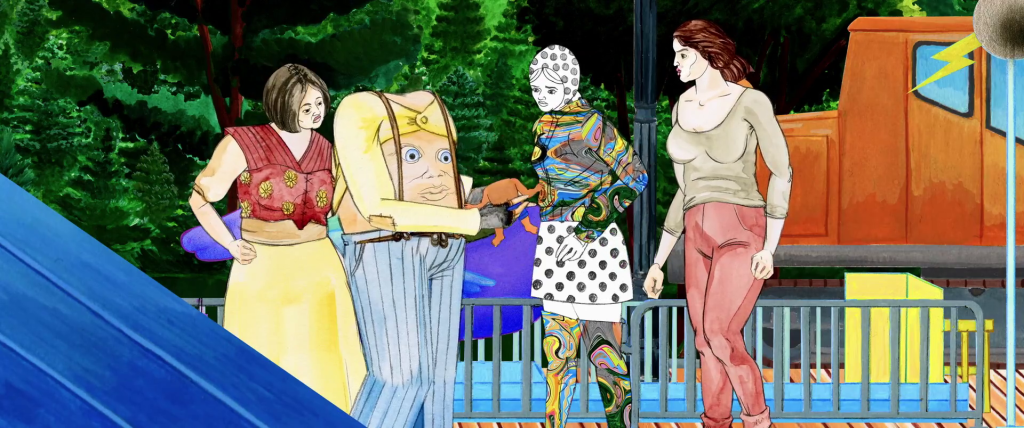

Cryptozoo

Should the collage-like, iconoclast graphical style seem distancing at first – and a bit too reminiscent of an older countercultural generation – take a while to let it sink in. Creative partners Jane Samborski and Dash Shaw put distinct touches of humanism in the realistic anatomy and faces of their subjects (human and cryptid alike), tethering our belief in their existence even as the film dials up its spectacle for the concluding third. With a grounded script and transparent premise that denies abstraction, I’d argue that Cryptozoo resists the lazy comparisons to an acid trip, as there’s a logic to every story and aesthetic choice, not to mention a quaintness to its internal philosophy that avoids getting too preachy. Yes, the story’s concerned with protecting innocent creatures from a threatening society, but so are many of the Disney movies that Shaw (like a lot of us) grew up dreaming about. This is epitomized through main character Lauren Gray (Lake Bell providing both voice and likeness), whose childhood-developed obsession with these paracosmic wonders becomes our surrogate viewpoint, examining the strange way our adult selves feel prone to place mistrust – and ascribe judgmental intentions – on the same flights of fancy that once brought us so much joy.

– 15 –

Riders of Justice

Deconstructing the action genre has become tropey in itself, and this Anders Thomas Jensen project has many conventional trappings, from a stone-faced antihero (Mads Mikkelsen, fascinatingly against type) as the straight-man to an offbeat ensemble (Nikolaj Lie Kaas, Lars Brygmann, and Nicholas Bro sharing an oddly quirky chemistry) who form an alliance of dubious motivations against an elite motorcycle gang. But the talented Jensen has something far more interesting up his veteran writer’s sleeve, and while he lays more than a few clear hints – and offers hardly any misdirection – on the path to his endgame, it’s all paced so slickly, and garnished with such crackling character moments, that it’s easy to miss how he’s played his audience along with his protagonists. Come the hour of reckoning, what’s assembled isn’t merely a satire, but what might just be a carefully planned – and tragically hilarious – takedown of the causality that’s at the core of cinematic storytelling, and our willingness to buy into plots that afford their players a singularly true course of action from what should be a random mess of circumstance. Luckily, we’re not denied our catharsis, for there’s much to admire in how this script’s solid entertainment serves only to enhance the metaphors on its mind.

– 14 –

Mass

With a screenplay revolving on a conversation between two sets of grieving parents (Ann Dowd and Reed Birney opposite Martha Pimpton and Jason Isaacs), both of whom see themselves as victims of a slowly-recounted tragedy, I was admittedly a little skeptical of whether Mass would justify its nearly two hour run-time. Thankfully, writer/director Fran Kanz keeps things engaging throughout, and makes the exposition (he doesn’t explain the setup beforehand, allowing it to surface through the confrontational dialogue) as convincing as the dramatic triggers. The four solid performances, threaded together by determined editing of their spoken and unspoken reactions, play the balancing act of stoking our biases against one couple or the other, only to later reframe our mindsets and ask us to re-examine our sympathies, without betraying what these grim events cost in real life. By the end, few answers are provided and more questions await down the road, but perhaps these four find within themselves what strength they need to move on from what they’ve lost, and forgive those who’ve left them behind.

– 13 –

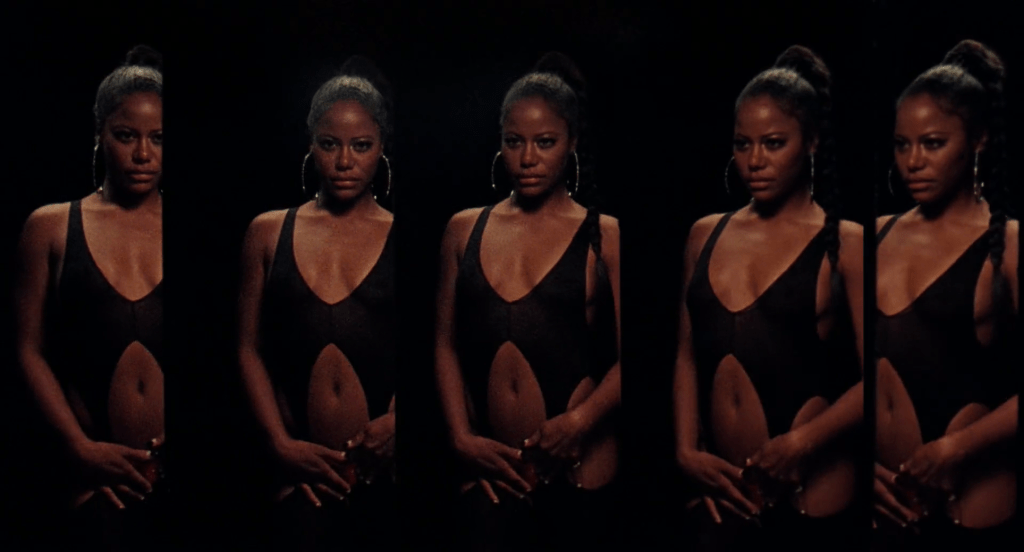

Zola

Shot with beguiling use of the 16mm format, stirred by the classical minimalism of one of Mica Levi’s best scores, and delivered with daring aplomb and audaciously ugly performances, this is the kind of film that offers a depth in style to match its subject. Based on a (possibly sensationalized) true story of a road trip wherein two dancers (Taylour Page and Riley Keough) fall into the seedier side of the club scene (represented by Colman Domingo), the steady-handed gusto of co-writer/director Janicza Bravo captures as much in what isn’t shown – or often, spoken – as in what is, allowing adrenaline and trepidation to build even in the quieter location shots and more wistful character beats that break up the criminal suspense. Elegant twists on old devices, such as the grotesque patchiness of the montages, or the delicately-composed long zooms that pulse with undertones of dread, draw a deceiving timelessness from the nascent source medium (a viral twitter-thread-turned-Rolling Stone exposé) and testify to how filmmaking can produce the most malleable of interpretations from the unlikeliest material. So much of what’s here feels like it shouldn’t work, but does, and Zola teases a wealth of inspiration from the gutters and cracks we overlook.

– 12 –

Titane

It’s clear that a good portion of Titane – namely the anatomical (and horror-tinged) exploration of Agatha Rouselle’s protagonist – has a lot that I’m not meant to fully relate to or appreciate. But that’s all good, as writer/director Julia Ducournau brings a ridiculously full plate of chic, sheen and substance to the table that offers plenty for any member of the audience to sink their teeth into. There’s a meditation on the meaning of transformations, mirrored by Ducournau’s own acceleration through shifting paradigms as we go from a jolting opener to a glitzy car show to a chaotic killing spree, all before the script’s true arc comes out of its shell; there’s a twisting look at the family construct, and its reliance on artificiality to keep itself bound; there’s a hypnotic rumination on music and dance, and its mechanical faculty to reveal, rekindle, and rejuvenate (to the rhythm of the Macarena, no less). And there’s the other anatomical exploration that I may not relate to now, but inevitably will: the supporting turn of Vincent Lindon’s aging firefighter, wrestling to reverse his own physical transformation over the fear of losing touch with what familiar comforts he has left.

– 11 –

Memoria

Filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s penchant for slow cinema is already a deal-breaker for some, and Memoria is no different. On top of that, it’s sure to lose a few audience members with the strategy of a “never-ending release” schedule, screening in one theater at a time for each week. It also arguably takes a higher degree of experimentation than his prior features, now concerned with the existentialism of sound and its eternal cycle of creation, transmission, internalization, and repetition. Oh, and (this is still a guess on my part) it just might be structured in a way wherein the crucial beginning and ending pieces of the story exist, but occur (mostly?) off-camera and beyond the actual scope of the script. Despite all this, if there’s one film I see potentially re-evaluated in future years and possibly moved up nearer to the top of the list, it’s this one. And – frustrating as the release schedule may be – if you have any interest in seeing it, I’d recommend somehow catching it in theaters, as I can’t imagine any home experience that could fully reproduce what Weerasethakul wants us to feel; much like the feeling that drives Jessica (Tilda Swinton), awakened by a noise that scratches at her memory and leads her on a path of discovery through the cityscape of Bogota. As Jessica’s sensitivity begins to inexplicably heighten, so too does the universe become less and less coherent. And so, too, does Weerasethakul further and further sedate the pace of his visual storytelling until it nearly reaches a standstill, freeing us to dive into our senses – and soak in what ambience we can before the breathtaking final impact.

– 10 –

Quo Vadis, Aida?

In the middle of the Bosnian War, Aida (Jasna Duricic), a schoolteacher from the municipality of Srebrenica, now works as a translator for the UN peacekeepers who’ve struggled to protect her besieged hometown. Frequently – often harshly – she’s reminded by her superiors to be accurate in her interpretations; to relay their declarations with utmost fidelity, particularly the strict orders they must enforce on the tired, displaced Srebrenica people who overwhelm their resources. To all of this, Aida complies, silently hoping that the value of her station will ensure her family’s safety – a need that becomes ever more pressing when their town is finally occupied by a brutal commander with genocide on his mind. Except that her usefulness begins to alarmingly turn against her, and more and more does she realize that the promises she’s being asked to translate have become lies; that both oppressors and protectors are putting on a theatre of words to disguise an inevitability they’ve mutually chosen to accept. As a character play wrapped in historical atrocity, Jasmila Zbanic’s film foregoes any explicit violence, and instead uses the unsettling capacity of language – in both speech and body – to bring the grievousness of these war-crimes, and the personal cost of conscience, into the light.

– 9 –

Red Rocket

That Simon Rex imbues the truly detestable Mikey Saber with such effortless watchability is Red Rocket’s first trick; the second is how filmmaker Sean Baker fully utilizes that cushion to double down on just how unforgivably bleak this character portrait should be. While no stranger to examining the American underclass, Baker’s subjects are usually those most trapped by their circumstances, and therein lies the key of Mikey being as much an alien visitor to the construct as we’ve ever had – one who (though he never shuts up) shouldn’t get to speak for this social strata. Sure, he came from messy beginnings in the city of Galveston (where Baker gets a killer choice of locations, all shot with his usual inventiveness), but we’re introduced to him returning there after spending 17 years in Los Angeles as an adult film star, one clearly convinced that his homecoming (and whatever unexplored mishap brought it about) will be as temporary as the Texas accent he’s long ditched. As we see him talk his reputation up to the same pedestal as the Hollywood elite, and witness how that confident grandiosity enables a sickening vision of everyone around him as an expendable co-star, we realize that Mikey’s cyclical trap may not be in his roots, but in his myth of the American dream, and how he’ll do anything to claim the genuine stardom he feels owed. There’s a third trick: how Rex slips in the faintest nuggets of Mikey sometimes waking from that self-built delusion, especially in his reaction to a guard-dropping number by the talented Suzanna Son.

– 8 –

Sabaya

Hogir Hirori executes what may be the year’s tensest and darkest thriller, as he documents the efforts of Yazidi humanitarians in northern Syria to find and rescue sabaya: women who were taken from their families at a young age and made sex-slaves for the Islamic State. Every step of the operation is recounted in harrowing detail, with the most critical piece falling on formerly-rescued sabaya who re-don their niqabs in order to infiltrate the ISIS-inhabited Al Hawl camp and locate other survivors of their lot. The most gripping of Hirori’s footage comes from cameras hidden under these women’s veils, capturing vividly the dangerous ISIS presence they endured as captives and must endure again as rescuers; the most impacting, however, are the recollections of the newly-freed women who make it back to the safety of the Yazidi Home Center, as they process the trauma of their experience and whether they can still rebuild their former lives. There’s plenty of controversy and debate already circulating on how this was all filmed, and that can understandably affect your choice on how to consider it. But it’s hard to deny the urgency of illuminating a largely unsupported situation, and the sobering ending makes it clear that what Hirori has released is only a minor link of a seemingly unbreakable chain.

– 7 –

The Summit of the Gods

While animation can – and should – be viable for any kind of story, it’s often perceived (at least in the West) as the means to take us beyond the limits of live-action production. But technology pushes those limits a bit further each year, to the point that mainstream blockbusters can now look to duplicate the delights of yesterday’s cartoons for a reliable commercial draw. What makes The Summit of the Gods so invigorating is how it intelligently finds a different way across that limit; many films have been made about climbing Mt. Everest, but here Patrick Imbert and his colleagues, in adapting Jiro Taniguchi’s 20-year old manga, take advantage of the hand-drawn medium’s infinite range of dynamic perspectives and its space to believably scale characters against the vastest environments conceivable. With crisp linework, tediously picturesque backgrounds, and an atmospheric rigor, they embellish a fictional – but no less personal – representation of the intensity, peril, and glory of a treacherous ascent, without diminishing the authenticity of nature’s most awesome opponent.

Habu Joji (voiced by Eric Herson-Macarel) has nurtured a toxic obsession to conquer the world’s greatest mountains, one that far outweighs any priority he has for genuine human connection. He aims to not only reach the ultimate summit, but to undertake the undoable feat of a solo climb up the Southwest face. As he locks into this life-defining mission, he withdraws deeper into his psyche and his pride, and the few bonds he might form turn into burdens to be cut loose – proving no small obstacle for the journalist attempting to track him down. So eloquent are the climbing scenes – the footfalls hitting with satisfying unease, the score strained with articulate yearning, the mountain shown in all its breathless starkness – that the question of whether or not we empathize with Habu becomes complicated to answer, and as the peak enters his sight, his triumph is illustrated all the more subjectively. We may not understand what drives him, but Imbert makes it defiantly alive.

– 6 –

The Humans

One of the hurdles of bringing plays to the screen is losing the essence of stagecraft, and the choices that surround this can often make or break an adaptation. With The Humans, Stephen Karam gets the rare chance to adapt his very own one-act play (about a family getting together in a newly-leased, mostly-bare New York apartment for Thanksgiving) as both writer and director, and he takes this task head-on to fully embrace its possibilities. The result is a stimulating approach to filmmaking, and my favorite directorial debut of a competitively crowded year. With a daring (but rewarding) use of atypical vantage points and unmotivated camera movements, Karam’s compositional angles fuse with the rickety art direction and continuously disorient us from any proximity to the Thanksgiving dinner we expected to join, almost as if we’re being dragged by our heels and placed in the viewpoint of a mystery observer who lurks behind the camera. There are many things this could mean, but I like to partly think of it as a way to replicate the fourth wall of the stage, while also threatening to break it and make us uncomfortable voyeurs of the family affairs that transpire.

There’s a fair share of sound and fury to the reunion, as of course there is; younger daughter Brigid (Beanie Fieldstein) turns vocal against the need to justify her pursuit of an artistic profession; her partner Richard (Steven Yeun) uses kindness and warmth to bottle his insecurities; older sibling Aimee (Amy Schumer) torments herself over a bad break-up and a troubling bit of news; and mother Deirdre (Jayne Houdyshell) and father Erik (Richard Jenkins) both grapple with being viewed as good parents who can refrain from judging their children’s choices. Also there is the dementia-ridden matriarch, nicknamed Momo (June Squibb), and her ramblings almost feel like a call to that same invisible presence who watches with us, and who is further empowered by the jarring footfalls of an unseen upstairs neighbor; by the almost precise failures of the creaky apartment’s plumbing and wiring; by the secret that Deirdre and Erik seem to be dancing around, which may or may not be related to Erik’s dreams of a faceless phantom. Things do become clearer by the end, and while the specter that haunts them stays hidden, it draws nearest in two affecting segments: one being a rotating long-take that finds the whole family truly united at the table, for the first and only time of the night, finally strong enough to address what really ails them; and the other finding a member alone, vulnerable and helpless in the dark, clinging to their last refuge. There’s thoughtfulness to how every bit of the medium works together to bring this film’s disquieting reflections to the fore, with a final shot that hints at us now taking the family’s place after their evening comes to a close.

– 5 –

The Power of the Dog

Jane Campion makes a tour de force return to the medium by adapting Thomas Savage’s period Western, whose plot focuses on 1920s ranch-owner Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch), his brother George (Jesse Plemons), and the widow (Kirsten Dunst) and son (Kodi Smit-McPhee) who’ll figure into their lives, as currents of animosity fill the dry air. The stakes are reservedly domestic, but there’s nothing less than staggering about the amount of craft that goes into every aspect of this production: the way the chapter breaks and vignette-like structure delineate a novelistic switching of perspectives, thereby mystifying as much as evincing each role in this drama; the way the lighting and palette track the change of seasons, and accentuate a similar change in mood (at least on the surface) from cynical to disarming; the way Johnny Greenwood’s disconcerting score fosters as much anxiety towards the serene majesty of the desert as it does towards the interpersonal mind-games at play; or the way the adaptation wisely spares us pivotal sections of the source material, intensifying our bewilderment at what unravels.

That’s all before getting into the stellar work of the cast, as Campion puts Cumberbatch in what at first seems an uncomfortable fit, only to later castrate his pretentiousness and have our perception – and the story itself – wickedly turn on that lever. Used to similar effect is Smit-McPhee, so unlike our image of the typical cowboy that we simply assume his arc lies in overcoming the mold of that ideal. Plemons leans into impotence with the right measure of empathy, and Dunst holds her own in a cold war with Cumberbatch, highlighted by a venomous chamber duel. But near the film’s middle, we briefly leave the arid desert to visit a lushly colored hideaway, where an interlude of startling prurience is punctured by a whispered secret; and this feels like such a visual and tonal relief from the preceding grimness that we’re tempted to take what is implied at face value, realigning and relaxing our theory of where the characters will lead us. Touches such as these are of a director at the pinnacle of technical skill, one who can corral even our sharpest instincts to a cerebral satiation – as she withholds any taste of the masterstroke for the very last second.

– 4 –

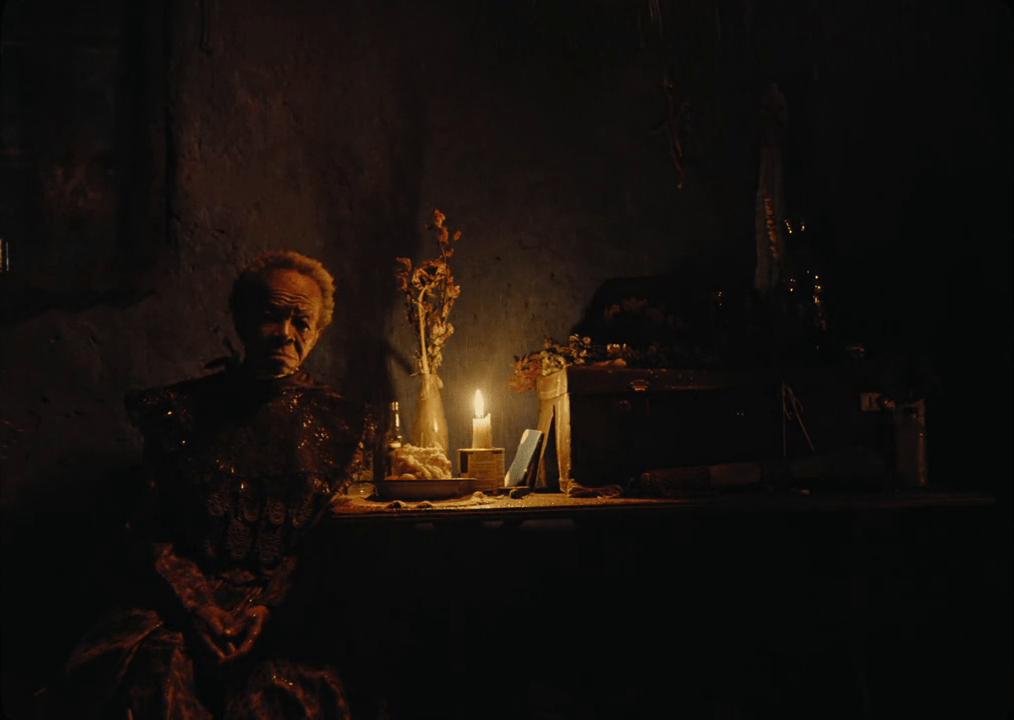

This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection

Much like its protagonist, Mantoa (Mary Twala Mhlongo’s final performance), This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection hides a tempest within itself that’s belied by the first impressions it gives. What is technologically sterile shows its archaic vigor in portraying this place and period; what monologues, establishing shots, and narrative chorus may start as repetitively stiff, gradually compound into the richly fertile earth from which episodes of evocative cinema arise. Adorned with a fittingly temporal design philosophy, and backed by a mournfully agitated score – both raising the thematic tensions between progress and stasis – this feature from Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese was the rare drama that, without striking any obvious chords, kept firmly in my thoughts after I’d seen it, and only grew in stature as time went on.

Mantoa’s plight is to deny the construction of a dam that will bring about the resettlement of her village and flood the ground where she wishes to be buried. While the premise feels intended to induce pity, each setback and obstacle added to the insurmountable only instills more vitality to the 80-year old widow’s decaying form. Frequently is she framed as but a minor, black-robed, plodding and often obscured figure against the film’s stunning landscapes, and amidst a community whose daily customs are being uprooted before her eyes – all of which she broodingly acknowledges will continue on after her death. Yet we never lose faith in her centrality to the events unfolding; perhaps from how her snaillike movements dictate the lingering nature of each shot, or how her supposedly-unheard prayers may be influencing the compositions towards strangely religious patterns. Pity feels like the furthest thing from our minds when she reaches her apex, and we brace to witness something biblical in the offing.

– 3 –

The Green Knight

One of my core beliefs about film is that the artform as a whole gets better with each year, and that’s what makes a picture like The Green Knight such a pleasure to take in. Made on a relatively humble budget, but allowed the space and commitment to thoughtfully experiment with its creative potential (and helped by an editing cycle that, though unintentionally protracted, may approximate the most obsessive of projects), it consummates into what could be the most beautiful film ever made. Yes, that’s an insane bar to set, and yes, there’s over a century of venerable artists who came before, but none of that is discounted given that director David Lowery, standing on the shoulders of his forerunners (and aesthetic collaborators), channels everything that’s been honed and passed on to create a fantasy of unrivaled immersion. There are no forced quotas of either grittiness or escapism here, but simply an exacting translation of the poem at its heart, allowing that sensibility to permeate with painstaking application to each textured backdrop, each lilting choral verse, each small piece of the environs that exists not in our world, but in the facsimile we might imagine when reading the tales of yore.

And that poetic influence is key, for in spite of the metatextual veneer, this film remains primarily concerned with the Arthurian legend of the title and all the bizarreness that entails. Sir Gawain (Dev Patel) has volunteered to be part of a knightly game that will lead him far through the land to find the Green Chapel, but it’s evident that participating with honor can only spell his gruesome demise. Lowery faithfully claims that counterintuitive premise, and trickles down its influence by similarly inverting other romantic traditions into tests to beset Gawain, literalizing the doubts and ambitions within him that threaten life or legacy, while puzzling us as to how the rules of this hero’s journey seem to reward what should be punished and exonerate what should be shamed. When the game is complete, what could have been a condemnation of medieval chivalry instead becomes an unearthing of the resilient ideals at its core, revealing how the most ancient of codes can inform the most contemporary morals, just as they can inspire such a state-of-the-art experience. This is a film that truly allowed me to lose myself in it, and made me wish it would never end; though when it did, it left me excited for the future works of its kind that will only grow worthier in what they set out to do, and I can’t wait to discover the next masterpiece that will take its place in the year to come.

– 2 –

The Worst Person in the World

These last two entries, though not as visually groundbreaking as the one before, are those that achieved in me the other feat of suspension for which movies are known: in the course of their run-times, and for hours-long reveries across the days (or weeks or months) that followed, they made me care about the fictitious lives of their characters over anything else that was on my mind. And while Joachim Trier’s latest may not be a fantasy (ostensibly it’s a comedy-drama), there is one technical showstopper of a sequence wherein lead character Julie (Renate Reinsve) escapes from the confines of living and into a wondrous reality that singularly sums up the themes of the film: to act without consequence or worry of anyone around us, to hold a moment that can last without the pressures of others as we chase our wanton desires, to be fulfilled with those we want to be fulfilled with and no one else. In other words, to be what’s called a self-absorbed narcissist, and while much has been said about this being an ode to the ills of young opportunists like Julie, there’s obviously more to it than that, as the symptoms are surfaced in every character regardless of their temperance, from her neurotic father (Vidar Sandem) to her older and more settled lover (Anders Danielsen Lie) to the virtue-signaling partner (Maria Grazia Di Meo) of the other man who catches her eye (Herbert Nordrum).

Late in the film, one of these personalities expresses a painful realization of why this could be so: a treatise on the meaninglessness of the present, how even the oldest of us need to look forward from what we have to find value, and how when that avenue closes, we’re left only to become absorbed and protective of what we’ve tried to make of ourselves, including the choices we’ve been told to regret. Heavy as that sounds, it’s from such dire foundation that the film’s purposeful script, in step with its precisely emphatic editing, gets so much mileage by expounding on the significance of what’s fleeting; by making marvelous tension from a faux-chaste meet-cute, by bathing us in the transient thrills of Oslo’s urban scene, or by hanging on to an agonizingly prolonged break-up and its desperately false attempts to find lasting solace. More than once, though, does life manage to catch up to Julie, and no punches are pulled in the devastating fallout, but that’s part of what makes her behavior – and Reinsve’s uncompromising performance – so easy to internalize and so challenging to turn away from; and so perfect a mirror, perhaps, for when we might feel like the worst person in the world.

– 1 –

Drive My Car

Every year, a film will remind me more than any other of why I’ll never get tired of watching movies, and it’s especially gratifying when – like with 2019’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire – that film can be a contender for one of my personal favorites of all time. It’s not just that Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s three-hour picture holistically embodies the tenets of filmmaking – there’s not a detail unutilized, no scene unneeded, not even a single sub-plot required as the lengthy script simply refuses to lose steam – but that these qualities meld flawlessly to form the vehicle of an emotionally epic drama, one that eschews traditional approaches of love and death for something uniquely redemptive. Hamaguchi’s screenplay is an expansion of Haruki Murakami’s short story, and while 2018’s Burning (another great film of recent memory) exemplified Murakami’s virtuosity of psychosis as a gateway to the surreal, Drive My Car could be the apotheosis of his predilection for the sentimental, and his lamentation for the impossibility of truly making peace with the past.

It’s best if I only hint at the synopsis here, since watching the setup is part of the experience (and let’s just say you might smile when the opening credits roll): we’re introduced to the seasoned stage actor Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and his screenwriting wife Oto (Reika Kirishima), who both have interesting practices for refining their professional techniques. Kafuku meets Koji Takatsuki (Masaki Okada), a television star who idolizes him, and later receives a request to direct a Hiroshima-based production of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. His involvement in the play will lead to the mysterious Misaki Watari (Toko Miura), a young woman the production staff has assigned as his personal driver, and to him facing a number of unburied ghosts that he’s kept suppressed. Other recurring features include recorded lines to Uncle Vanya that play constantly on a cassette tape; multi-lingual rehearsals frustrated by restrictive acting methods; a fable of a girl and a lamprey that’s steeped in sexual intimacy; a mute actor, Yoon-a (Park Yoo-rim), whose delicate handle for Korean sign language gives voice to those struggling to unburden themselves; and, of course, the car of the film’s title, a distinctive red Saab that Kafuku maintains in immaculate condition. Each of these components is so deftly integrated into the larger themes that their placement elicits captivation from even the barest readings, keeping us fully engrossed while becoming layers upon layers for the engine of the narrative, as our characters are steadily mobilized from the hum of their internal contemplations until they reach crests of riveting power. And Hamaguchi of course brings the technical facets along for the ride: the shot compositions initially unassuming, but sharpening in their symmetry and symbolism with each added mile; the audio starting at a leisurely diegesis before tuning in slowly towards the enigmatic. One grace note of the sound design startles with a Chekhovian shock to punctuate the most nerve-wracking scene in the film; another commands the world to hold its breath and fall as mute – and as free of burden – as Yoon-a.

But this is a drama above all else, and multiple levels are at work in just how brilliantly the cast rises to the challenges set by Murakami, Hamaguchi and Chekhov. Okada’s character intimidates performatively in an early scene when he auditions for a menacing role, then proves equally chilling, but on an entirely different wavelength, when he later comes down from the stage and eventually delivers what is sure to become one of the great cinematic confessions. Miura coats the young Misaki with a cosmetic hollowness at the outset, but tenderly develops that demeanor in carefully chronologic consistency up to her last on-screen appearance. Nishijima brings a profound solemnity to the guarded Kafuku, somehow capturing a vague loneliness even in a scene where he and Oto make passionate love, but then unleashing volumes of restrained torture in the climactic monologues. And Park Yoo-rim is unforgettable when given the spotlight, elevating our notions of non-verbal acting into one of the year’s most arresting performances. With all that said, I know there’s so much to this I still haven’t wholly taken in: whether in the motives behind the actions of these characters, or the implications of the inactions that defined them; the importance of Uncle Vanya, and all its intended parallels; the fragments we hear of Oto’s stories, and how they stem from her own passage of grief. I may never reconcile these in full with how the film already makes me feel, but that doesn’t take away from the ability of its text to delve deep into the soul – and bring out the real from within.