Always I fall way behind when I try to do an all-in-one recap of twenty or so films at once – this year is no different and I’m still a week late (and one of these has already released wide), but it helped that I took more immediate day-by-day thoughts. And thankfully my lineup delivered – with both high-profile (for the festival) and lower-key, more-likely-to-be-missed releases, almost all of which I was happy to catch.

I thought of foregoing a ranking this time, but I think I have one I’m comfortable with.

26 – Went Up the Hill

dir. Samuel Van Grinsven

New Zealand

Vicky Krieps sinks her teeth into a psycho-horror dual (of sorts) turn that layers a subtle mania with her soft voice and ethereal pathos. This could go well with the oedipal premise – a gay son attending the funeral and meeting the girlfriend of the mother who seemingly abandoned him – but the direction’s on a somber wavelength that freezes out any spontaneity, and Dacre Montgomery doesn’t have much chemistry with Krieps, struggling noticeably more than she does through pretty clumsy material (the scene that introduces the “ghost” actually has him ask “Who are you?” and the ghost matter-of-factly answering). In the Q&A after, Krieps describes her character as “fun”; I can sort of imagine that vibe on set, but not a lot makes it into the final edit. She came on stage during the credits to perform a song she wrote for her character – a moment that unsurprisingly had more impact than the movie itself.

25 – Happyend

dir. Neo Sora

Japan

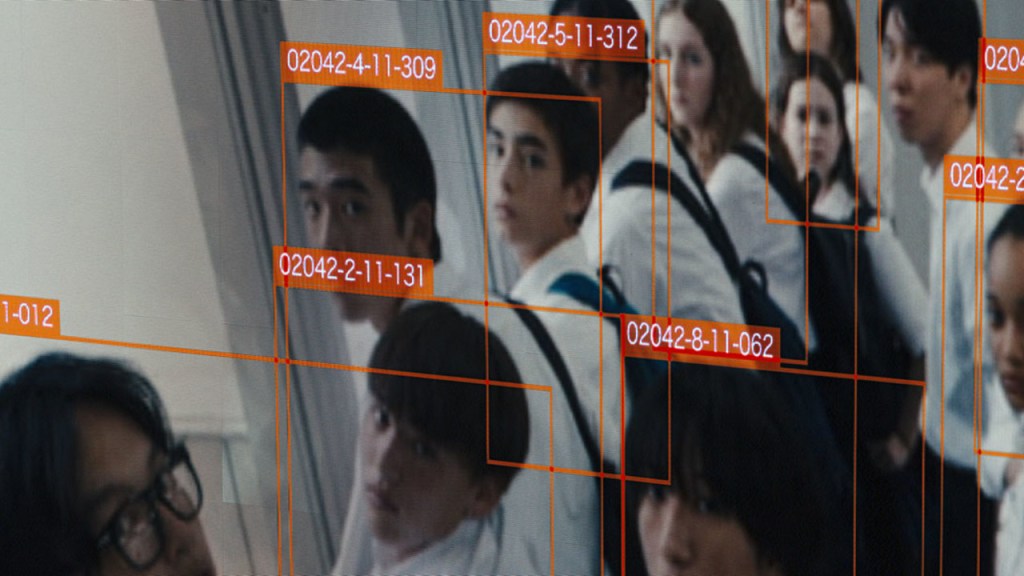

In a “near future” Japan that’s grown increasingly paranoid and xenophobic, the faculty of a high school tightens its rules and places students under constant surveillance. But this doesn’t turn out to be the dystopic thriller you might expect; just as most of the school kids here are less concerned with the actual changing environment and more invested in their personal issues, so is the film content to settle on the everyday drama of them challenging the system in individual ways rather than build a broader exploration of its themes. Overall, the political stuff is there to sketch out the narrative and force some conflict, but the air is kept light with little in the way of complications. Neo Sora based this on his own high school experiences; I imagine it works better if you’re closer to that frame of mind.

24 – Pedro Paramo

dir. Rodrigo Prieto

Mexico

I’m not familiar with the Juan Rulfo novel it’s based on, a forerunner to the likes of Gabriel García Márquez; but given the figurative devices around the haunted legacy of a philandering Mexican lord, something feels lost in Rodrigo Prieto taking a slightly pedestrian approach that’s closer to Innaritu (there’s even the Emmanuel Lubezki floating camera) than his more indulgent projects. And though it starts off with a nonlinear structure, some chronological back and forth, and genuine enigma and misdirection, the story itself eventually demystifies into standard patterns that shed the more lyrical, diverting aspects. It’s still undoubtedly pretty directorial work – but it does come off as safer and less colorful than some of the early-going suggests.

23 – Emilia Perez

dir. Jacques Audiard

France

So this one apparently received mixed reactions. I’m probably closer to ambivalent, but I admit to having a decent enough time more than I didn’t. The ending’s a mess, Selena Gomez makes a would-be emotional throughline entirely ineffectual, and I don’t know if any of the musical numbers are actually good (more Sondheim faux-recitative, with rhythm that reminds me of Ana Tijoux, and no I never would have guessed that Camille supplied the songs) but they’re hardly boring or incoherent, and weirdly I can hold them at a remove from the rest of the movie without that being a detraction. That probably makes no sense for a musical, but it’s where I land. Jacques Audiard’s films generally miss more for me the wilder they get, and this goes very wild, but he draws an old-fashioned workhorse performance from a committed Zoe Saldana, and Karla Sofia Gascon is a fully believable, unexpected balance to her titular character’s provocation of all the surrounding chaos.

22 – Nightbitch

dir. Marielle Heller

USA

Marielle Heller’s one of my favorite directors of the past decade, her body of work both holistically diverse and individually non-conformist while drawing on the foundational strengths of each sub-genre she explores. All that said, I think I’ve liked each new movie from her just a bit less than the last, and while that’s mostly depended on my interest for the choice of subject matter and stylisms, what struck me here is how cipher-y most of the supporting cast to Amy Adams feels, especially Scoot McNairy’s self-absorbed archetype of a husband. That may arguably be in the movie’s ballpark – crossing the mainstream family comedy with an off-beat (and half-trashy) suburban fable that’s vocally and visually forthright. Heller’s habit of establishing her voice, world, and style as early as possible helps to make this nearly as seamless as her “cleaner” films, despite juggling a less conducive flow of ideas and tropes.

21 – Meat

dir. Dimitris Nakos

Greece

A director’s debut feature shot entirely in handheld, with a fairly small cast and stripped-down, naturalist aesthetics – these limitations used to efficiently draw us into the small-town drama and its decidedly personal stakes. A Greek family and the Albanian boy who works at their butcher shop get wrapped up in manslaughter and have to figure out who takes the fall, as tenuous relationships with both their neighbors and each other start to crumble, and there’s just enough bite to the unraveling dynamics and encroaching judgment to shoulder the run-time at a brisk pace. It might start to repeat itself before the end, but it maintains the right amount of wariness and uncertainty to keep us on edge.

20 – I, the Executioner

dir. Ryoo Seung-wan

South Korea

This is the first feature I’ve seen from Ryoo Seung-wan (and no, I didn’t realize it was a sequel to a previous film, because that’s how much I choose to ignore program writeups), so I might be more impressionable than others to his hyperbolic directing style. But he hooked me pretty quickly, the pumped-up opening sequence at a female-catering gambling den having more than a few flashes of brilliance in the fashion of Takashi Miike, and with enough of an identity of its own to feel fresh. It does come down a bit from that for the rest of the film, but the mechanics are solid: a comically-eager homicide department ends up on the wrong side of vigilante justice, making for a buddy cop “drama” that progressively edges darker before steering into action set-pieces in the John Wick mold – which it integrates with earnest logic and uses to brutal emphasis.

19 – Viktor

dir. Olivier Sarbil

Ukraine

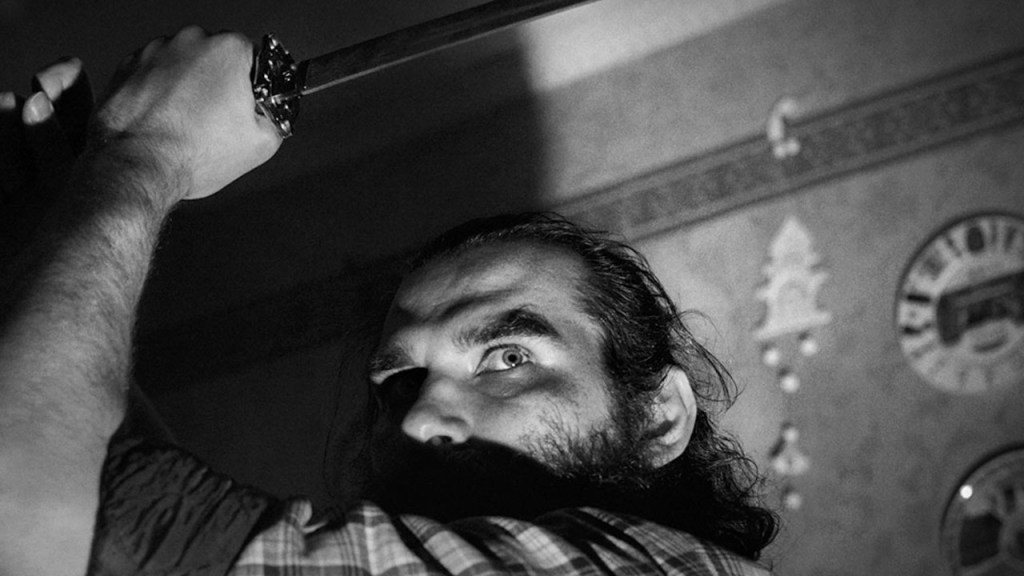

Sensitive documentary about a deaf Ukranian who’s grown up yearning to serve his country as a soldier – and gets the chance to join the battlefield as a war photographer. They dated this as little as possible; it was actually conceived by Olivier Sarbil long before the current phase of the Ukrainian war began (he’d met Viktor in the early 2010s), and the focus never once leaves Viktor himself who, regardless of what a more global context associates, is not forced to stand in for any kind of demographic or minority. Instead we’re left uncluttered in his headspace, and involved in his small discoveries of both the narrowing locality and of himself (like how he takes naturally to the firearms he’s never held before). The black and white allows Sarbil’s footage to blend with Viktor’s high-contrast photography, and directs more of our attention to the sound design as it recreates the effect of his impaired hearing, including an internal monologue that’s closer to vibration than vocal.

18 – The Quiet Ones

dir. Frederik Louis Hviid

Denmark

Maybe not a lot here for people who aren’t already interested in the genre, but there are some solid, dependable kicks for people who are. It’s based on the real-life largest heist in Denmark’s history and does go into the logistics of how it happened, but doesn’t overdo the exposition, more evoking rather than explaining the complexity and danger of what’s in the offing. The characters are all largely based on the actual perpetrators and not even vaguely glittered-up, with just enough notes of humanity to carry the flesh, blood, and consequence to hold our connection. It builds up to the climactic operation with similar restraint; there’s a moment towards the mid-point where an aerial highway tracking shot suddenly pulls back to give us our first wide view of the city, and that probably does more than anything else to suggest at the scale of what’s about to go down – itself an exercise in tension and chaos than satisfaction. Afterwards, I read a review out of curiosity which complained about how a female character introduced near the outset ends up “shoved aside”, which I think is a pretty summative misunderstanding of how to see this film; smart and sparse in its choices, and neither obvious or obtuse.

17 – Grand Tour

dir. Miguel Gomes

Portugal

Miguel Gomes’s riskiest and most interesting project, and perhaps most nebulous in terms of purpose. This time he’s drawing from an extremely obscure, 1918-set account of two Western epistolarians on a circumstantial “tour” through several cities across Asia, but the film’s conceit is to use present-day documentary-like footage for each city (captured on-location by Gomes) to establish its identity and placement in the story. None of the footage has an intended thread outside of what Gomes found visually entertaining at the time, so your mileage may vary – as will your take on its juxtaposition with narrative scenes that are knowingly shaped by the Orientalisms of the early 20th century. But there’s some convincing golden-age shine to this, especially when things perk up at the halfway point and we switch from dour adventure fiction to screwball Hollywood. There’s a lot here left to chew on; I think it’s more about whether what you see, and how it’s put together, appeals to you enough to find the configuration that suits your tastes.

16 – Flow

dir. Gints Zilbalodis

Latvia

Breezy, kinetic, pastel-rich animation that lets you either take in and muse over the thematic worldbuilding in its backgrounds and minutiae, or just enjoy the story of lost animals trying to get home – except this time “home” is a land that’s been swept away by flood. As someone who had to come around on describing “cinematography” in animated movies, that’s definitely the highlight here, in a very good way; the low-angle camera frames the immensity of the land from the perspective of our tiny protagonists, with long tracking takes that precisely respond to the momentum of their skitterish impulses, all making the wordless odyssey so effortlessly immersive and enjoyable.

15 – The Brutalist

dir. Brady Corbet

United Kingdom

I’m more distant to this than others, but the film itself is not distancing at all, fully open-hearted and involving the audience in its process and schematic for Brady Corbet’s take on the Great Post-War American Novel (with all the appropriate baggage that entails). The first half is as classic as it gets in following a displaced Jewish architect (Adrien Brody) who finds a reason to buy in to the Camelot analogy; it’s the second half that really made things memorable for me, the faults in the dream coming from areas not as evident as I thought. And it may also be Corbet’s most personal work as a filmmaker, where it’s easy to draw the parallels of ill-deserved happenstance, destructive partnerships, organizational frustration, and deep-seated traumas that all somehow contribute to the grand thing you are trying to build, whose completion and fulfillment rarely comes in the way you’d envisioned. Joe Alwyn was my personal big surprise here among the cast.

14 – Perfumed with Mint

dir. Muhammed Hamdy

Egypt

A highly metaphorical Cairo where we spend most of our time hanging out with characters smoking hashish or, alternately, hookah flavored with mint leaves grown from human flesh (exactly what that sounds like), and ruminating on religious-inspired epiphanies and poetry. Like Pedro Paramo, this is another film by a cinematographer-turned-director, but Muhammed Hamdy well goes one over Prieto, letting his visual instincts fully take over to deliver some of the most gorgeously-minimalist, chiaroscuro-laden slow cinema that carves deeply textured, canvas-like shots from the simplest of atmospheric and tactile combinations – smoke, barren buildings, dirty bathrooms, some ingenious use of perspective to both layer and segment a shot in lieu of camera pans that are exceedingly rare. As a methodical, eerie, abstracted example of a twilight world engulfed in ennui, I found this delightfully hypnotic.

13 – Sunshine

dir. Antoinette Jadaone

Philippines

One of the best depictions of modern Manila that comes to mind; seedy, shrouded, overly lived-in, bustling and branchingly-confusing, this brings out the sweltering spirit of the city and its Hugo-like dimension as an earthly cross of Catholic heaven and hell. And that suits the story of a poverty-raised Olympic hopeful finding herself with an unwanted pregnancy, steadily ratcheting into full desperation with no bearings to guide her. Except it still doesn’t feel as heavy as similar films with this predicament, more anxiously electric and almost devilish in its humor. A mental projection follows the protagonist around to coax and chide, and this at first feels like something the film doesn’t need, but after a while I bought its importance. As enlightened as the modern Filipina would be, the inherited conscience and guilt is heavy and the pressure of this situation can be even stronger from within than without. The ending might be one scene too long, but the penultimate moment epitomizes how deeply rooted this mentality is.

12 – Queer

dir. Luca Guadagnino

Italy

I think this may be my favorite, and I would say one of the best, of Luca Guadagnino’s films, though it didn’t start out that way; the first third or so, while well put together, felt formalistically stuffy and stereotypical of a literary-minded period piece, and Daniel Craig’s character honestly struck me the same way…and then we take a considerable turn where everything off-putting and artificial starts to coalesce; I’m reminded of my perspective shift on Benedict Cumberbatch in The Power of the Dog. From there things break loose into a broad, meandering, attention-divided road trip that, even as it frequently embraces hallucinogenic dream sequences and subjectively tight viewpoints, finds a consistent psychological and emotional resonance in Guadagnino’s strength as a filmmaker – which is his sensory (more than sensual) understanding of the relationships of bodies to each other, and this features some of his strongest endeavors to enhance that dimension while finding inventive ways to play with the dynamism that the medium allows it.

11 – Hard Truths

dir. Mike Leigh

United Kingdom

They gave this one a content advisory for bullying, and I can see that warranted because it really, really doesn’t let up. There’s room to find humor in how verbally brutal Marianne Jean-Baptiste’s character can be to everyone around her, but there won’t be enough oxygen to go round before too long, and our lack of an anchor to the film outside of her leaves us constantly wincing against her existence. It’s a testament to how intense Baptiste’s transformation is that we feel as exhausted as she sometimes looks, a mood enabled by Mike Leigh’s arrangement of detail and fluidity to each scene (even the camera’s weight feels almost ominously minimized) that gives his characters more room to breathe than the space seems to allow. The dialogue is dense, both in scenes with Baptiste and without her (lighter ones which Michelle Austin carries fluently, and one in particular with Ani Nelson set in a workplace, almost tangential to the rest of the film, that really stood out) but a lot of the real work and effort comes when we pull back into silence and see just how everyone takes to that. Singularly-pitched as this might feel, it’s just graceful enough to remain compelling throughout, and any moments of relief are measured sparingly to the picture’s bleakness.

10 – The Seed of the Sacred Fig

dir. Mohammad Rasoulof

Iran

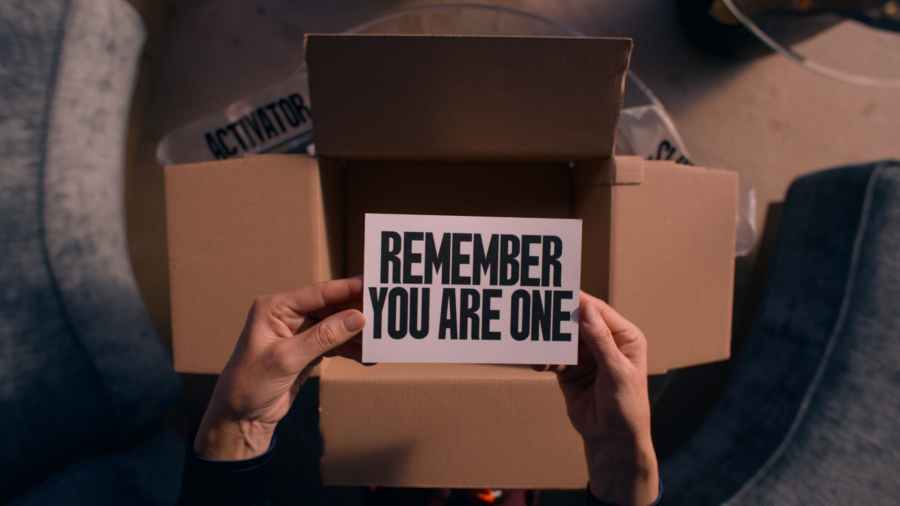

Beginning as a removed portrayal of a very real moment in time for Iranian culture and politics (marked by a tragedy that occurred only 2 years ago, which makes me curious about the production cycle), this centers on a family that embodies the divide between those who find solace (and power) in religious structure versus the younger generation waking to counter its oppression, as a mother (Soheila Golestani) tries to reconcile the life of opportunity she and her husband have strived for with the violence and torment on the streets that’s quickly approaching their doorstep. There’s plenty to engage with from that alone, but then we come to the midpoint and pick up a literal loaded gun that takes aim internally and, without betraying what came before, forces a repositioning of the message from a pure institutional critique to a deep-seated, more unforgiving struggle of undermining power dynamics older than God. Chilling stuff out of Misagh Zare and Golestani, the latter a precarious timebomb of a character study and one of my favorite performances of the year.

9 – Julie Keeps Quiet

dir. Leonardo van Dijl

Belgium

A very strong debut about a young tennis student (Tessa Van den Broeck, legitimately impressive as a teen athlete) who’s working through unresolved demons left by her former coach. As the title implies, the throughline is unpacking what’s keeping her from opening up to others about it. And it may not just be the trauma of the event, but partly the oasis that comes with being the competitor who’s had to work for more than she’s given to get to the top, only for the privilege of her talent to be curse and blessing on self-guidance, no matter how personable and grounded she might be. The film wisely doesn’t try to make this a portrait of a flawed personality; there’s no unhealthy sense of ambition getting in the way, but just youth, and inexperience, and the pressure of not wanting This Bad Thing to mess up the whole future that’s in front of her. The 16mm lends a practice-footage-type quality to the tennis, which itself is unconventionally filmed without close-ups, slowdowns or highlight shots of player’s faces or connecting rackets; instead it keeps a fixed, one-sided, court-level perspective even during competitive matches, the camera steadily panning across and back to track offensive and defensive alternations – well in the vein of the fight within Julie’s own mind.

8 – Paying for It

dir. Sook-Yin Lee

Canada

Flavored like a blend of Funny Pages and Terry Zwigoff (moreso than those two are already linked), including a quirky precision towards filling in the margins of Toronto’s urban strangeness, but without trying to outdo the essence of either and going its own way and moral. For the uninitiated: Chester Brown’s a Canadian underground cartoonist who in 2011 wrote about his very-real choice to quit on relationships and just start seeing prostitutes. It’s honestly a great read, but this film is directed and written by his last girlfriend, Sook-Yin Lee (who he breaks up with at the beginning of the book/film), which made me wonder if it would put a new spin on his actions, and refreshingly it doesn’t. What it does do is expound the context with a wider and more inclusive perspective on liberating sexual politics from their ties to romantic love, and whether or not that sits well with you, the film keeps its opinions inwardly focused on its pitiable characters and their own warped predicaments (Sook Yin-Lee’s stand in going through a decade-long depressive spiral), and in so crafting a modernist love story that enhances the source material’s profound honesty and idealistic affirmation.

7 – On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

dir. Rungano Nyoni

Zambia

The sort of ambitious second feature that you’d hope to get from a director who seemed to be holding back the undercurrents in I Am Not a Witch. A patriarchal figure turns up dead on the street; his niece Shula (Susan Chardy), her cousins, and other women connected by his grisly habits are forced into hosting a funeral that none of them feel positive about – especially if it absolves the private vices he inflicted on them all. Rungano Nyoni once again places her characters in roles of gendered esoteric irony, the same core themes seeping right through a deranged viewpoint of a floodlit urban dominion. It feels that women silently occupy every murky corner of the layers and facets we see, yet often fall prostrate to the ground and allow men to overpower them even after death. Her dead-eyed cynicism is very much on the surface, dredging up images that scratch the mind as they visualize right on the cusp of the hyper-real, and relying on Shula’s sourness to offset any kind of elevation that might take us out of her acidic family nightmare.

6 – Anora

dir. Sean Baker

USA

Sean Baker’s most heightened project so far, which may be called for as it inverts the usual formula: after being mere suggestions at the fringes of his working-class world-systems, here the uber-wealthy finally step out of the shadows as harbingers of the radioactive toxicity that only money can buy – complete with a doomsday clock set to their hour of arrival. The starting pace is almost vulgar in how it smashes through the motions of a false-footed meet-cute, taking breaks only for snippets of oblivious elegance as Ani (Mikey Madison) and her hapless would-be paramour (Mark Eydelshteyn) tease each other with sex and power (and both dial their grip on reality way, way down). When we finally reach the turning point, and the sense of how far we have to fall sets in, it’s actually a relief for this second half to delay the inevitable and spin off into circular episodes of aimless mayhem, with old-fashioned slapstick and farce thrown fearlessly in the face of a very rude awakening. The cast may not be as formidable as that of Red Rocket, but they’re overflowing with charm (which is what’s more important here) and Madison locks into a magnetically physical performance and presence – eventually excising the foregoing rollercoaster into an emotional fallout of an ending that you just need to sit with.

5 – Horizonte

dir. César Augusto Acevedo

Colombia

It may speak for a contemporary Colombia, but what comes to life is archaically literary and cinematically classical. In a purgatory (or perhaps a shared dreamscape) that resembles a gritty battlefield, a mother and son search for the father but are waylaid by metaphysical obstacles tied to the pain and blood that’s formed the land they walk on; the significance of their attachments to these is made known, and their path towards any kind of reconciliatory outcome is consequently re-shaped, adding intrigue to the journey that eventually reaches just the right amount of poetic payoff. Naturally the imagery does the heavy lifting; the countryside alternating between rustic and luminant, the grandeur of our panoramic field of vision framed by meteorological effects that feel biblical (there’s meticulous CG design used in just the right doses), and I like how none of it tries to get too heady, abstract, or overly allusory; I’m sure plenty of details flew over my head, but everything’s underpinned by a semi-mythic series of motifs that give direction to what’s intended, allowing them to reverberate as they come in and out of play. And though the meaning may be clear, the use of dialogue in the cadence of a Greek chorus, to continually question and challenge our ideas between what is truth and what is only perceived, retains the mystique of its final form.

4 – Misericordia

dir. Alain Guiraudie

France

A powder-keg of incisively liberated dramatics. A man returns to his hometown to attend the funeral of the local baker and give condolences to the baker’s wife and son, who then suggest that he take over the business. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything to say that all of this is barely a factor and just an excuse to get things rolling. There might be common ground with his prior features in terms of what unfolds, but Alain Guiraudie’s touch is in how much delight he has with confounding our read of the tone he’s going for. The key here is just how well he uses Felix Kysyl (another of my standout performances from this year), whose lead turn is almost frustrating to put a finger on, as he switches from enigmatic, pathetic, absurdist, and chilling – not in any logical progression but as a deceptively moving target between them all. That carries through to Kysyl’s interplay with the eccentric townsfolk, subverting the order of things as an obscure object of perhaps not desire, but unhealthy fixation (or even confusion) for their bizarrely motivated personalities. And Claire Mathon applies the familiar palette she developed in Petite Maman, now recalibrated to long-seeded cravings that bear a harvest of twisted intentions.

3 – April

dir. Dea Kulumbegashvili

Georgia

Duality is marked from the onset. Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili) serves the Georgian healthcare system as a licensed ob-gyn, then ventures out under cover of night to sustain a more illicit practice; the bare sketch of a plot hinges on both the failed outcome of an unmonitored pregnancy, and the operation urgently required by a sexually-abused deafmute; and while Nina speaks resolutely of her compulsion to preserve the greater breadth of life, in her mind’s eye she may view her existence – and its necessity – as the sort of abomination that should’ve died at birth. It’s no surprise that the film isn’t willing to reassure her; perhaps sometimes she may be a monster, the mental and emotional scarring of her vocation leaving her numb and blind to the ugliness of an impaired world, and left to the same indignities in her daily cycle that others of her sexuality experience. But the filmmaking meditates with her to find a karmic balance that the narrative withholds; her psyche framed through first person ruminations of the mundane surroundings, her essence and imprint contemplated in patiently-captured footage of the fertile elements of a weathered landscape – a figurative deity of the Spring kept at an intercession between the lands above and below. No doubt there’s a lot here to start outward political discourse; hopefully that doesn’t subsume the conversations about what the craft itself accomplishes.

2 – The Substance

dir. Coralie Fargeat

USA

This won’t be for everyone – not just because of the body horror, which is a diet of the usual dysmorphic gross-out mixed with some more morally questionable (but undeniably effective) ingredients I wasn’t expecting. But also for Coralie Fargeat’s storytelling sensibility, which works in a sort of loop: she tees up the scene, hits you with the gag, and then goes a few more rounds to seemingly play it out, often kicking things up a couple of notches to the point that it feels excessive…then again to the point of almost daring you to think of why she’s being this excessive, before closing the loop and moving on. I daresay you can break the film up into a sequence of said loops that lead into each other. Personally I don’t think there’s an inherent flaw to this, but the trick is whether she can earn it each time, using these protracted stretches to tilt our emotional angle, or pull a fast one on our expectations, or to just stay and relish the moment. For a lot of instances it’s that last case, and that can only work for a filmmaker as technically gifted and manically fascinated as Fargeat is proving to be – enough to explore all the nuts and bolts of any given gag in her slowly-built aesthetic arsenal, rather than throwing them away like many filmmakers would almost as a rule. There’s one brief close up of Margaret Qualley sipping a Diet Coke that’s shot like a commercial, but it’s the sound of her slurping that jumps out as needlessly, coherently polished.

Look, I’m probably in the tank for Fargeat. I relished these protracted moments and getting sucked right into the bigger, overarching loop of Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley’s ouroboros around the whole narrative – again set up with what feels like an overload of visual emphasis, only for those same cues to be humorously hammered at us when their payoffs come due. Though I can see how this is meant to be a reversed anti-female-body-shaming cry, it veers dangerously close to being maybe-morally degrading – but knowingly so, and part of that big loop is pushing hard enough until we check our conscience at the door, leaving just enough heart for genuine anguish over Moore and Qualley’s self-immolating decisions. This is a fairly long movie for its type of material at 2 hours and 20 minutes, and again, that final 20 minutes will objectively feel stretched out – but it’s that very same protracted part of the larger loop that left me weightless, queasy, and cluelessly smiling by the end. I don’t think you’ll guess just how far she pushes the gag here. Speaking for myself, I’m glad she did.

1 – Caught by the Tides

dir. Jia Zhang-Ke

China

It was only in the introduction before the screening (given by Jia Zhang-Ke and Zhao Tao themselves) that I learned what this project was about; I can’t say for sure, but I wonder whether or not it’s better to come in unprepared. In any case, this remains quintessentially Jia: the sweeping generational scope of Mountains May Depart and 24 City (and the latter’s documentarian viewpoint), weaved together with A Touch of Sin‘s threads of class displacement and intracultural conflicts, and the yearnings of unresolved promises from Ash Is Purest White. As much as it’s the usual showcase for Zhao Tao, more clearly than ever is her story a parable for Jia’s contemplation of China; in her unfazed soul is the people’s ageless indomitability and capacity for transformation revitalized, her broken relationships a reflection of their being locked and bound to the machinations behind the country that have long wrestled its identity and heritage into something much narrower and more singularly-minded.

A forceful reckoning between the two is depicted at several points, each turn with a different outcome to mirror cultural motions within history, and gradually making clear how and why the backdrop of the country’s recent years inspired the stitching of this tapestry together. And even when the flickers of the past are sparked from more insular or obscure touchstones, the references feel universal; Jia finds the minor synaptic connections from his own memory (and perhaps shared with our collective conscious) that only the cinematic medium can trigger, in formats that we today consider primitive, but which kindle no less of a wellspring under his artistic fingerprint. He’s been making a recurring joke on the festival circuit about how he has to wear sunglasses now because of how taxing the editing process was on his eyesight. I can definitely buy that.

Less self-evident, but just as embedded, in this whole experiment is Jia and Zhao’s own personal history of a changing relationship with – and perception of – the medium; while they may have already been at the forefront of what’s termed the 6th generation of Chinese filmmaking, herein they harken back decades to the same burning desire from when that movement was new, the same sort of inspiration to reveal and rebirth the echoes, songs, and violent flashes of memory, unmoored from the need to reprove, before they’re fully lost to time. Some memories that feel they’ve been held on to for so long, waiting to be furnished in a more naked truth than may have previously been allowed. And something infectious in how they’ve given their lives to cinema and, in the process, given cinema life. It would seem in that sense like a summation to this stage of their careers – were it not for just how much of a step forward the final act is, even when compared to the stirring conclusions they’ve previously delivered: cold, angry, otherworldly, almost, in its look and sound and as elusive as it gets.